The Proto-Germaic verb would have been *þankjan the /j/ caused umlaut in all the forms which had the suffix subsequently the /j/ disappeared. (These verbs have a dental -t or -d as a tense marker, therefore they are weak and the vowel change cannot be conditioned by ablaut.) The presence of umlaut is possibly more obvious in German denken/dachte ("think/thought"), especially if we remember that in German the letters and are usually phonetically equivalent. Examples in English are think/thought, bring/brought, tell/told, sell/sold. The German word Rückumlaut ("reverse umlaut") is the slightly misleading term given to the vowel distinction between present and past tense forms of certain Germanic weak verbs. Often these are subsumed under the heading "ablaut" in descriptions of Germanic verbs, but their origin is distinct. Two interesting examples of umlaut involve vowel distinctions in Germanic verbs. On the other hand, German spells Känguruh ("Kangaroo") with an, although the origins of this vowel have nothing to do with umlaut this is an English loan-word, and the diacritic is being used in mimicry of the English grapheme-phoneme relationship.

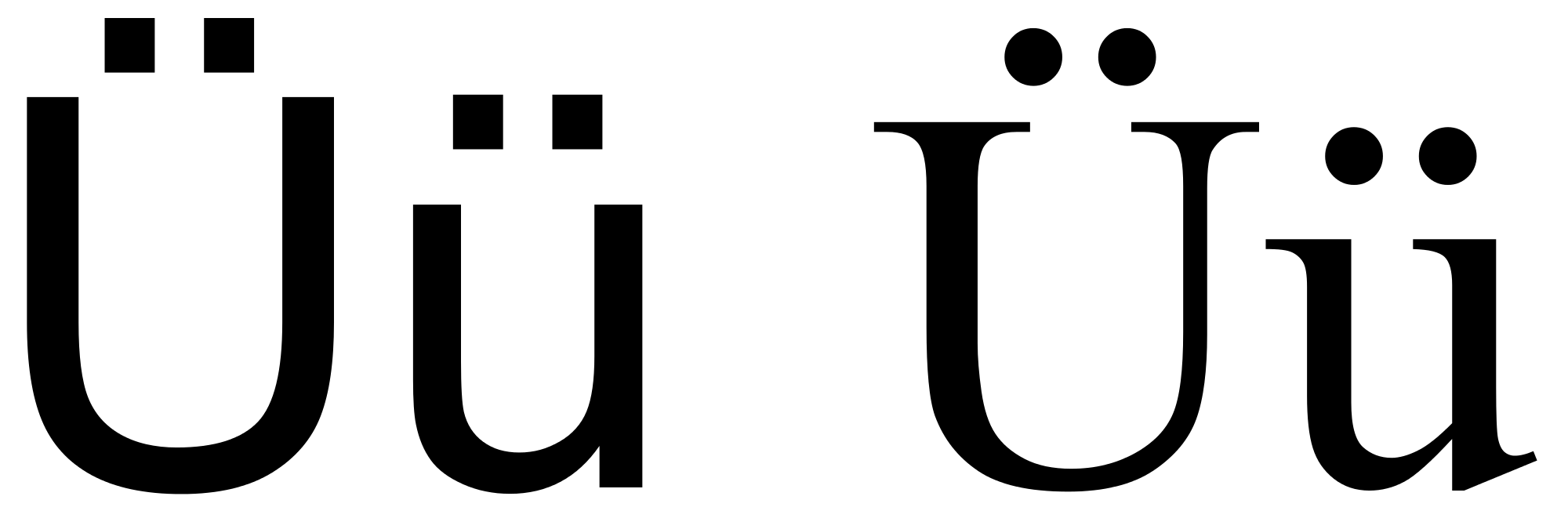

The adjective fertig ("finished" originally "ready to go") contains an umlaut mutation, but it is spelled with e rather than ä as its relationship to Fahrt (journey) has for most speakers of the language been lost from sight. (On the phonetic realisation of these, see the article on German phonology.) However, German orthography is not entirely consistent in this. The result in German is that the vowels, , and become, , and, and the diphthong becomes : Mann/Männer ("man/men"), lang/länger ("long/longer"), Haus/Häuser ("house/houses"). Because of the grammatical importance of such pairs, the German umlaut diacritic (see below) was developed, making the phenomenon very visible. Likewise, umlaut marks the comparative of many adjectives. In German, umlaut as a marker of the plural of nouns is a regular feature of the language, and although umlaut itself is no longer a productive force in German, new plurals of this type can be created by analogy. Umlaut is conspicuous when it occurs in one of such a pair of forms, but it should be remembered that many English words contain a vowel which has been mutated in this way, but which does not now have a parallel unmutated form umlaut need not carry a grammatical function. In English, such umlaut-plurals are rare, but other examples are tooth/teeth and goose/geese compare also long (adj)/length (n). The suffix caused fronting of the vowel, and when the suffix later disappeared, the mutated vowel remained as the only plural marker: men. We can see this in the English word man in ancient Germanic, the plural had the same vowel, but also a plural suffix -ir. Umlaut should be clearly distinguished from other historical vowel phenomena such as the earlier Indo-European ablaut (vowel gradation), which is observable in the declension of Germanic strong verbs sing/sang/sung.Īlthough umlaut itself has nothing to do with grammatical function, the resulting vowel changes often took on such a function. This process took place separately in the various Germanic languages starting around 450 or 500 AD, and affected all of the early languages except for Gothic. In umlaut, a back vowel is modified to the associated front vowel when the following syllable contains, or (the sound of English ). The term umlaut was originally coined and is principally used in connection with the study of the Germanic languages. In linguistics, the process of umlaut (from German um- "around", "transformation" + Laut "sound") is a modification of a vowel which causes it to be pronounced more similarly to a vowel or semivowel in a following syllable. Vowel modification Germanic umlaut Template:Diacritical marks

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)